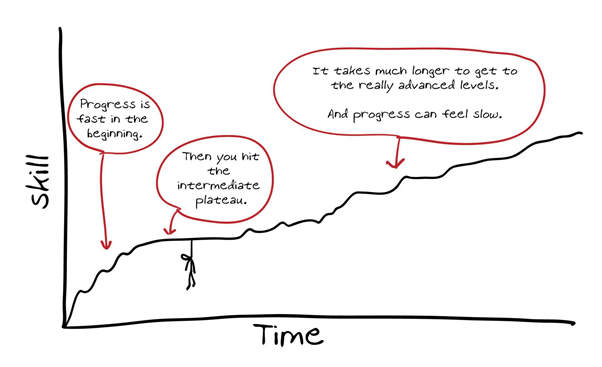

Many of you will be familiar with the word ‘plateau’ as a word that you can use to help you describe line graphs in part 1 of the IELTS writing exam. Here, according to the Longman Dictionary, plateau can be described as ‘a period during which the level of something does not change, especially after a period when it was increasing’. So, you might be able to guess that the ‘intermediate plateau’ refers to a period of time when a learner seems to make little progress and finds it difficult to reach an advanced level of English. In this blog post, I will try go give some reasons for the intermediate plateau and also suggest some solutions about how to overcome it.

First of all, the main reason for the intermediate plateau is that a comparison is being made with the lower levels of language learning. As a beginner with close to zero ability (in anything), it is usually quite easy to make progress fairly quickly and to also notice this progress, which brings a sense of achievement. This is because when you start out with no (or close to no) ability in something, it is almost impossible to not feel a sense of progress. After all, you cannot get worse if your ability started out at zero! However, once you get to intermediate level, you already have a level of ability and so your point of comparison is much higher, making it more difficult to notice any improvements in ability.

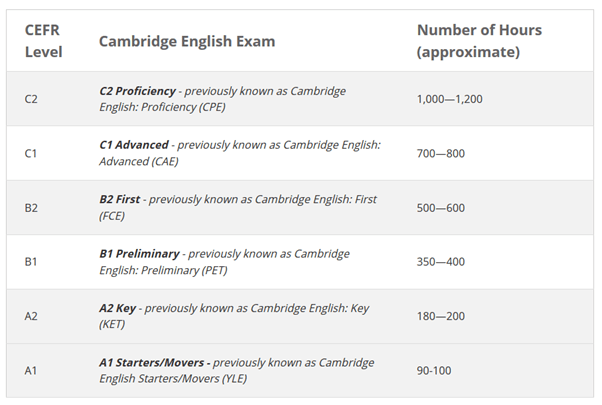

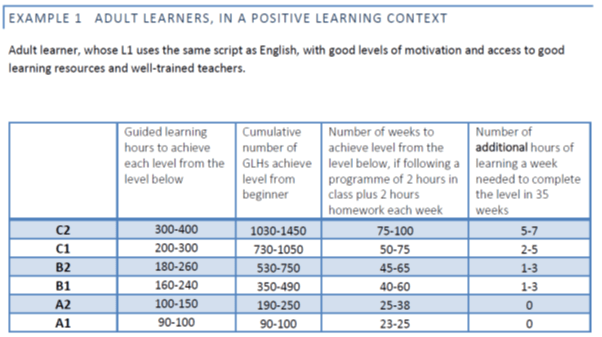

Secondly, when you start out as a beginner, the words you learn are usually some of the most common words in a language and you will see these words over and over again (because they are the most common!). This means that you do not need to read or listen as much to get the repetitions you need to help these words to be stored in your long-term memory. Therefore, you need fewer hours of input (reading and listening) to help you progress to the next level. This is reflected in the research, as if you remember my final blog post about how long it takes to learn another language, it is suggested that it takes fewer hours to progress to the next level at lower levels of learning:

Another possible reason might be to do with motivation. When we start out learning something new, motivation is usually quite high at the beginning. However, over time it is quite natural that these levels of motivation begin to drop (often they are at a level that is unsustainably high to begin with) and so, with lower levels of motivation, it is normal that less time is spent on learning and it therefore takes longer to get through the intermediate stage compared to the lower levels.

It is also important to be aware that language learning does not progress as a straight line and so there will always be some ups and downs along the way, which may mean that progress is harder to see. For example, one indicator of an advanced learner is the ability to use more complex grammar and vocabulary. However, in order to be able to use more complex language in speaking and writing, learners need to try to use this new language. Obviously, in trying this new language for the first time, mistakes are made in the process (maybe more mistakes than previously), but these mistakes are just a natural (and even necessary) stage that learners need to go through in order to progress to the next level.

However, it is also possible that the so-called intermediate plateau doesn’t really exist at all. The reason I say that is because it might be that the type of language that learners need to get to an advanced level is more difficult to notice and measure than the type of language that is required to get from beginner level to intermediate level.

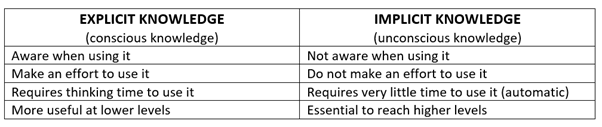

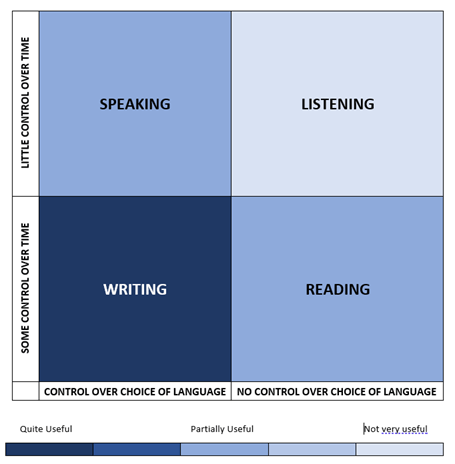

If you remember from my previous blog post about implicit and explicit language knowledge, explicit language knowledge is much more useful at lower levels when learners don’t have any language knowledge at all. However, implicit language knowledge is essential to get to higher levels such as advanced level. Therefore, it might be that learners at intermediate level are having trouble changing their focus from developing explicit language knowledge to developing implicit language knowledge. If learners at intermediate level continue to focus too much on developing explicit language knowledge, then they are likely to be disappointed and feel frustrated at their lack of progress.

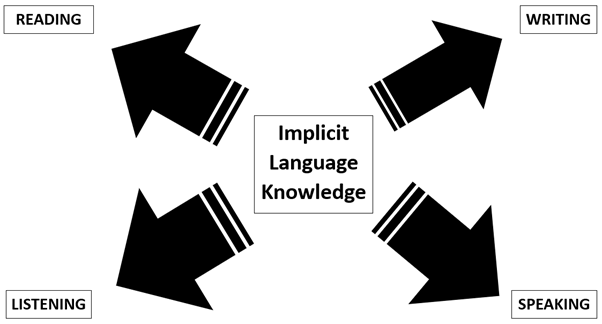

Also, as explicit language is easier to notice and measure, there is more of a sense of achievement in developing explicit language knowledge. However, when learners are developing implicit language knowledge by reading and listening, for example, it is much more difficult to feel the benefit and the improvement in developing implicit language knowledge. This may be one reason why many learners spend too much time focusing on explicit language knowledge as it feels more like learning than developing implicit language knowledge. However, we must remember that learning a language is not like learning other subjects or skills and so we should be prepared to learn it in a different way.

On to solutions then, which some of you may already be able to guess. If you are an intermediate level student who is preparing for the IELTS exam, one of the best things you can do is be patient. Do not set yourself unrealistic goals of when you might be able to achieve a score of say 6.5, for example. Accept that it is going to take time to reach your goal and don’t panic. Some students try to rush the process of language learning because they have a specific target in mind to achieve by a specific time. Under these circumstances, it is quite common for students to try and study really, really hard, i.e. do lots of grammar exercises, learn lots of new (and mostly useless) words and do lots of practice tests. However, doing these activities are unlikely to help that much in developing implicit language knowledge, which you need to reach the higher bands of IELTS. Instead, focus instead on doing lots of extensive reading and listening, which might not feel like ‘learning’, but will actually lead to much greater benefits in developing your language skills in the long term.