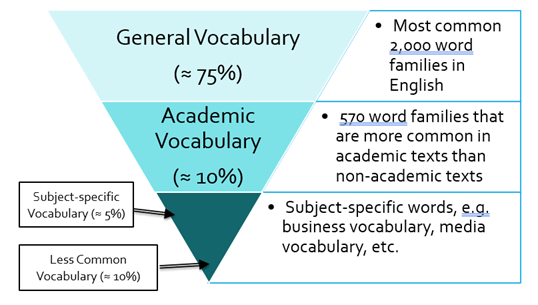

In the last blog post, I explained how you could use dictionaries and text checkers to identify useful vocabulary to learn and remember. In that post, I focused on the 3,000 most frequent words in English. However, to get to higher levels of English, achieve a high score on the IELTS and to be able to read academic texts at university, you will need to know a lot more than 3,000 words.

According to Nation (2006), you need to have a vocabulary of about 6,000 to 7,000 words in order to have a good understanding (98% of all words) of a spoken text such as a movie, whereas for written texts such as novels and newspapers, this increases to about 8,000 to 9,000 words.

Before deciding on what words to focus on, it might also be useful for you to do a vocabulary size test. You can do one at this website and it should take less than one hour to complete.

You might also be interested to know how many words you need to know to be at each level of English. Now, this is a difficult question to answer as it depends on how you measure when a learner knows a word. For example, there will be a big difference between receptive vocabulary (what you can understand, i.e. in reading and listening) and productive vocabulary (what you can use, i.e. in speaking and writing).

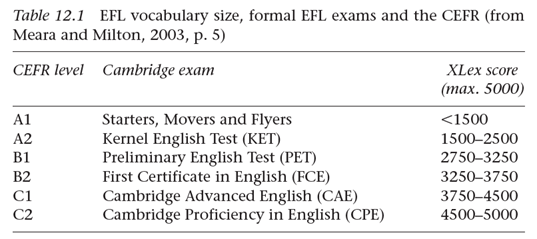

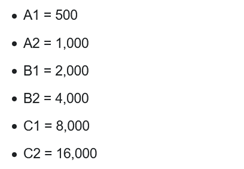

The only research paper I could find gave the following estimates for vocabulary sizes:

However, I am a little unsure of these numbers, especially at the higher levels as most C1 level learners could probably understand most words in a film and even in novels that are not too difficult. Therefore, I would expect the vocabulary level to be higher at both C1 and C2 level, especially as very few learners ever achieve a C2 level of English.

Although this is not an academic source, so perhaps less reliable, I found the following discussion online and I feel that some of the estimates here to be more realistic, e.g.

This estimate suggests that the number of words required doubles to reach the next level rather than increasing by about 500 words for each level. Although this is not based on any research evidence, the above estimates do seem to be more likely than the previous estimates, especially for the higher levels.

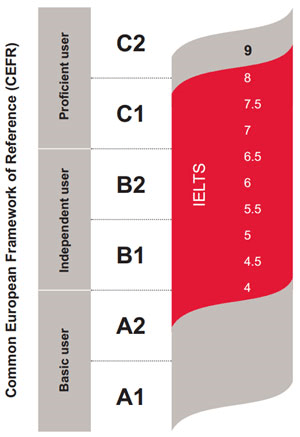

As a useful reference, the image below shows roughly how the different CEFR levels (A1-C2) relate to the IELTS exam. Whichever scale from above you use, it is clear that you are going to need over 3,000 words to achieve a score of 6.5 or higher on the IELTS test.

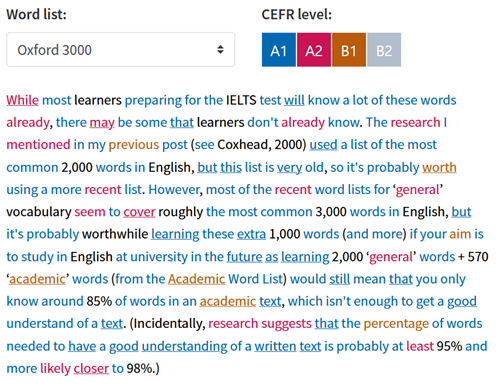

In the previous post, I mentioned the Oxford 3000 list. There is also an Oxford 5000 word list, so if you think you know most of the words at the 3,000 word level, then it would be worth focusing on the additional 2,000 word on the Oxford 5000 list.

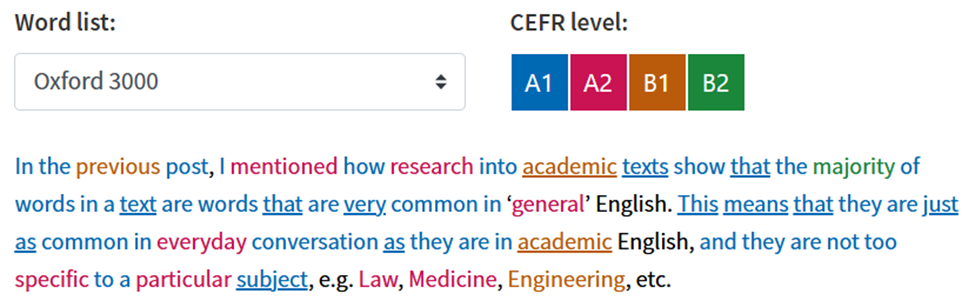

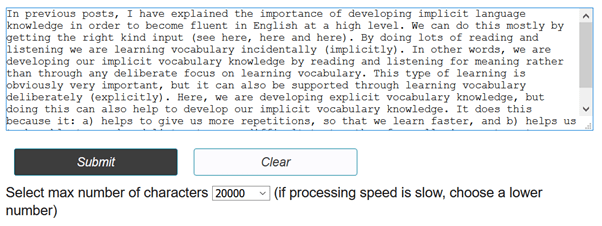

As with the Oxford 3000, we can also use a text checker to find out what words are on the Oxford 5000 list by copying and pasting a text into the box, e.g. below shows the results (up to B1 level) for the Oxford 3000 list.

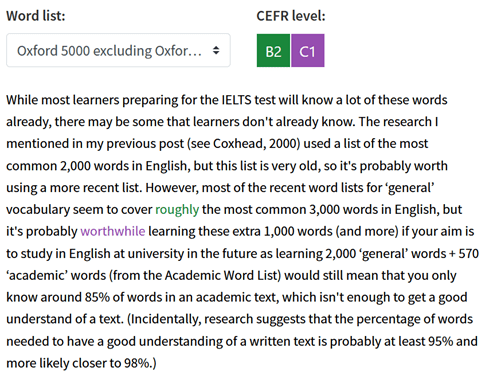

And below shows the results for the Oxford 5000 list (B2 and C1 level), not including all the words at in the Oxford 3000 list.

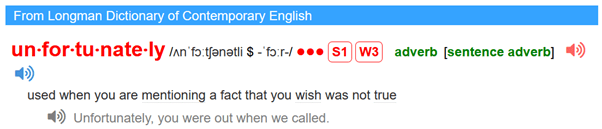

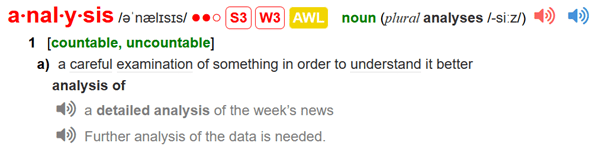

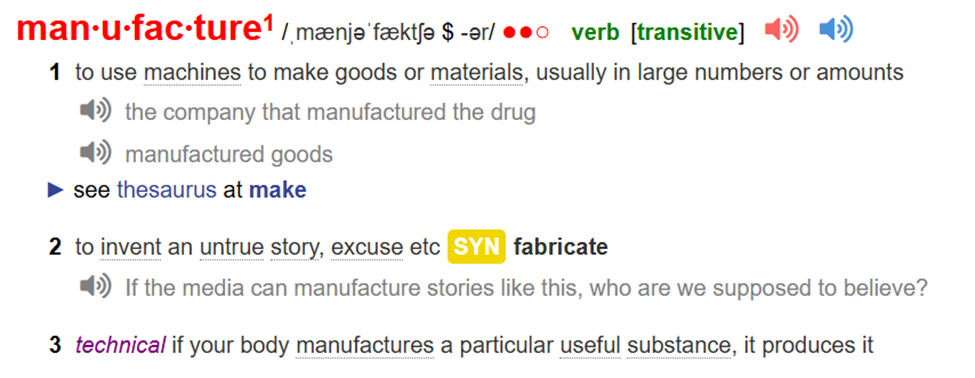

If you are high-level learner (C1-C2 level) and want to learn more than the most frequent 5,000 words, you can also use the Longman Dictionary that was mentioned in a previous post to find the most common frequent vocabulary. As can be seen below, the Longman Dictionary sometimes has red circles next to each word.

Three red circles represents:

- High Frequency (0 to 3,000 most common words)

Two red circles represents:

- Medium Frequency (3,000 – 6,000 most common words)

One red circle represents:

- Lower Frequency (6,000 – 9,000 most common words)

If we search for the word ‘manufacture’, we can see that there are two red circles next to the word, which shows that this is a medium frequency word:

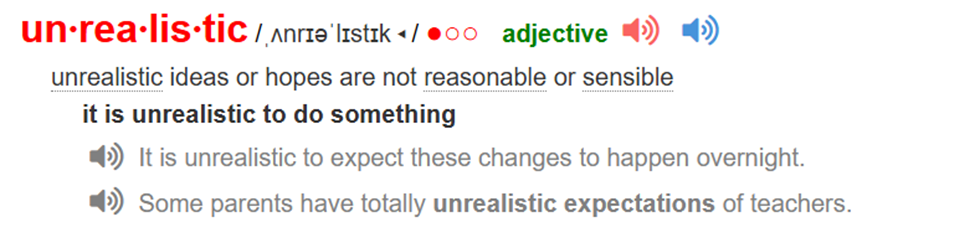

Likewise, if search for the word ‘unrealistic’, we can see that there is one red circle next to the word, which means it is a lower frequency word, but still one of the most common 9,000 words, so it might be useful for advanced level learners.

However, vocabulary lists are probably more useful when they are either for higher frequency words (as the lists are more likely to be accurate) and for specific vocabulary. Therefore, you should be careful about using these lists as the reliability of them depends on the kind of texts that have been used to create a database of language. Whilst I would assume that these dictionaries have quite reliable databases, there will be some differences, especially for lower frequency vocabulary as they won’t have used exactly the same texts.

It is also worth mentioning that this kind of self-study activity should only be one part of your vocabulary learning. An even bigger part of your vocabulary learning should be through getting lots of input as I have shown in previous blog posts (see here and here).

References:

Milton, J., & Alexiou, T. (2009). Vocabulary size and the common European framework of reference for languages. In Vocabulary studies in first and second language acquisition (pp. 194-211). Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Nation, I.S.P. (2006). How large a vocabulary is needed for reading and listening? Canadian Modern Language Review, 63(1), 59-82.